On Ukraine, Biden Is Dead Right to Ignore the “Do Something” Crowd

Whenever global trouble boils, our foreign policy big shots say U.S. credibility is at stake unless we act. Alas, the record shows that acting is often where the problems start.

Excerpts from a column by Michael Cohen in the New Republic.

“Do something.”

This is the mantra of the foreign policy pundit class when practically anything happens in the world.

There’s a civil war in Libya. “Do something.”

A humanitarian crisis in Syria. “Do something.”

China is ramping up pressure on Taiwan. “Do something.”

And today, as Russia seemingly prepares to invade Ukraine, the response has been the same. “Do something.”

Yet as the Ukraine crisis continues to unfold and, increasingly, all sides appear to be seeking an off-ramp from war, the United States may have averted conflict not by doing something but rather by doing nothing.

To understand why, it’s important to take a brief sojourn in the shoes of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Anyone who tells you they know precisely what the heck he is thinking is probably not worth listening to, but several issues seem clear.

Putin is concerned about NATO expansion to the east and has been for some time. It’s arguably the reason his military forces invaded Russia’s neighbor Georgia in 2008, not long after NATO announced at the Bucharest Summit that it was opening the door for membership to Georgia and Ukraine.

In the current crisis, Putin has repeatedly demanded that NATO take membership for Ukraine off the table, which the West has refused to agree to, for fear of being seen as giving in to Russian pressure.

Putin also appears to be aggrieved at the ongoing westward tilt of Ukraine, which includes not just potential NATO membership but also accession to the European Union. Indeed, it hardly seems like a coincidence that Russian aggression toward Ukraine—including the seizure and annexation of Crimea in 2014 and support for pro-Russian insurgents in the country’s Donbas region—began not long after the Maidan revolt, which toppled a pro-Russian president. And as Ukraine has moved closer to the West—elected pro-Western presidents and taken measures like deemphasizing the teaching of Russian in school—Moscow’s aggression toward its Western neighbor has ramped up.

So let’s assume for the sake of argument that Putin’s focus on Ukraine has less to do with territorial gain and more with maintaining Russia’s sphere of influence in its near abroad and limiting the West’s political and security ambitions in the former Soviet Union.

What, then, could he potentially glean from the West’s response to the current Ukraine crisis? Predictably, the U.S. and European nations have threatened Putin with major economic sanctions if his troops enter Ukraine. This, of course, was the Western response to Putin’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, so the threat can hardly come as a surprise to the Russian leader. Then the U.S. organized economic sanctions that had a crippling impact on the country’s economy in the near term, but over time Moscow has weathered the storm. One has to imagine that Putin has factored in the potential for more sanctions as he considers a military foray into Ukraine. If sanctions didn’t dissuade him in 2014, it’s hard to imagine that they would work in 2022. Aside from military intervention, it’s hard to imagine what the U.S. and NATO could do to deter Putin from going to war.

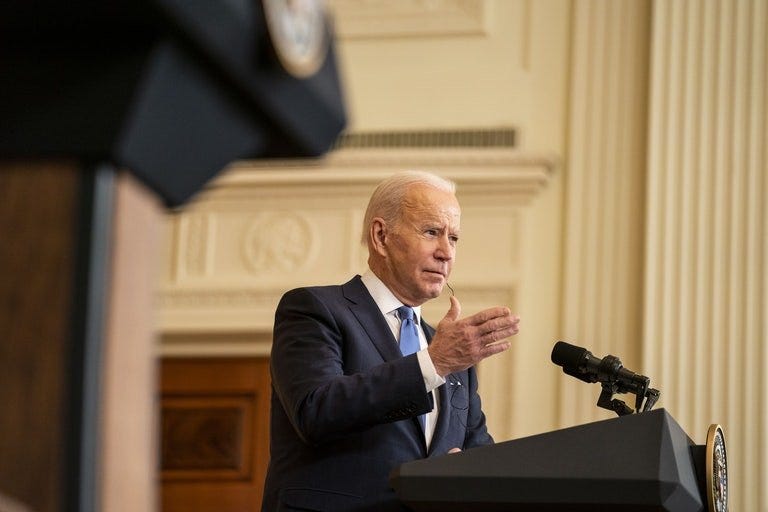

But what is likely of greater interest to Putin is what hasn’t happened. President Biden made clear, from the outset, that he would not be sending U.S. troops to defend Ukraine. Few voices in the U.S. foreign policy community demanded that he do so. Instead, 3,000 American troops have been mobilized to Poland and Romania, two key NATO allies.

In a January press conference, Biden said that Ukraine would not be gaining NATO membership anytime soon—a point emphasized this week by French President Emmanuel Macron. Even fears that a Russian invasion of Ukraine would lead to Finnish or Swedish accession to NATO aren’t materializing. In January, Finland’s Prime Minister Sanna Marin said it was “very unlikely” that the country, which shares an 832-mile border with Russia, would apply for NATO membership during her term.

Sweden’s foreign minister has made clear the issue “is not on the table” in the near term for his country. All that could change if Russia invades Ukraine, but for now it doesn’t appear that Putin has much to fear from NATO creating a beachhead on his northern border.

Finally, if Putin’s gambit was intended to sow dissension within the ranks of NATO members, that hasn’t worked, either. NATO has spoken with one voice on the conflict, and member states have signaled a willingness to follow the U.S. lead on punishing Moscow if Russia acts against Ukraine. If there are cracks in the alliance, they are not evident.

So if Putin’s goal in this crisis was to seek clarity on the West’s ambitions with NATO and the alliance’s views on a Russian sphere of influence in its near abroad, he has his answer: The U.S. and the West will do the bare minimum to stop him.

That might seem overly simplistic because sanctions are not nothing. But when it comes to the question of whether the West will put real skin in the game, it’s clear that—with the possible exception of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—NATO countries are not willing to go as far as the Russians might have feared. If the West isn’t willing to defend Ukraine now, when the potential for Russia invasion and occupation could not be more real, it’s hard to imagine when it might.

Indeed, the very fact that the U.S. is sending troops to Romania and Poland, creating in effect a cordon sanitaire, shows that Biden is far more concerned about spillover from a war in Ukraine than Ukraine itself.

This also sends an explicit message to Kyiv: that the U.S. and Europe will offer rhetorical support but not much more.

This is not to suggest that the U.S. strategy toward Ukraine was conceived to send such a clear message to Russian leaders about its intentions in Eastern Europe. Rather, its effectiveness lies in its implicit nature. By publicly identifying the limitations of U.S. national security interests and by making clear where the country’s political priorities lie, Biden has sent a powerful, albeit subconscious, message to Putin. The U.S. will not interfere in his perceived sphere of influence. It will not defend Ukraine militarily from Russian aggression. It will stand up for Ukraine, but it will only go so far in doing so and not at the cost of American blood and treasure—and that’s a view shared by even the president’s critics. And it will prioritize the security of its alliance partners.

If Putin were to recognize the implicit message being sent by the U.S. and NATO, he’d see that he’s basically won this round. In fact, it comes on the heels of even more indication that the West is willing to grant Putin a free hand in his near abroad.

Two years ago, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Belarus, in what was seen as an effort to potentially create distance between Moscow and its erstwhile Western ally. Six months ago, Western governments were offering public support for anti-government protests.

Yet last fall, when Putin sent Russian commandos to the Belarus-Poland border, the move brought hardly a response from the West. Even the sending of tens of thousands of Russian troops into Belarus—in what is viewed as a move to encircle Ukraine—is provoking anger not because of the impact on Minsk, but rather for Kyiv. Western leaders are tacitly acknowledging that Russia has a free hand in Belarus.

Yes, Putin is not getting an explicit statement closing the door on NATO membership, which he clearly prefers, but the U.S. has put its cards on the table when it comes to a Russian sphere of influence in its near abroad.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that Putin gets the message. Moreover, for political reasons—domestic and international—he may still decide that he needs to “do something” to make the saber-rattling of the past several months all seem worthwhile.

But if Putin wants an off-ramp from war—and a reason to believe that NATO’s eastern expansion is likely over and his sphere of influence is recognized in Western eyes—all he needs to do is read the tea leaves.

If that happens, it will represent a significant victory for Biden. He will have avoided war and made no explicit concessions to Putin. In fact, ironically, it may appear that he effectively deterred Russian aggression, even if he will have implicitly conceded key ground to the Russian leader. The “do something” crowd may be disappointed that there’s been no ostentatious display of “strength and resolve.” But sometimes in international diplomacy, less is better than more, and nothing is better than something.

Michael A. Cohen is a columnist for MSNBC. He writes a newsletter on American politics and foreign policy called Truth and Consequences.